Nilgiris

Botanical Gardens > Nilgiris

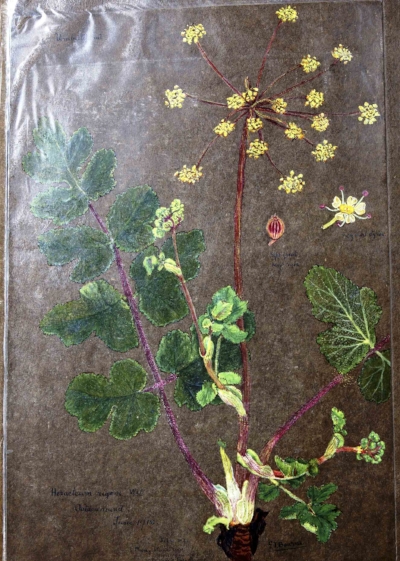

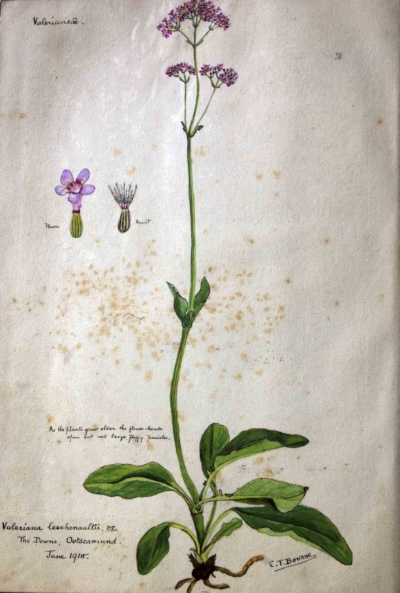

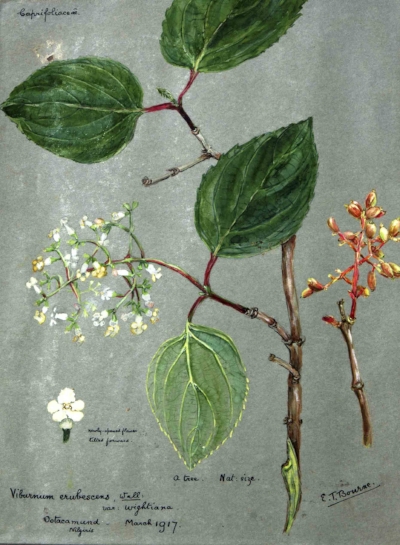

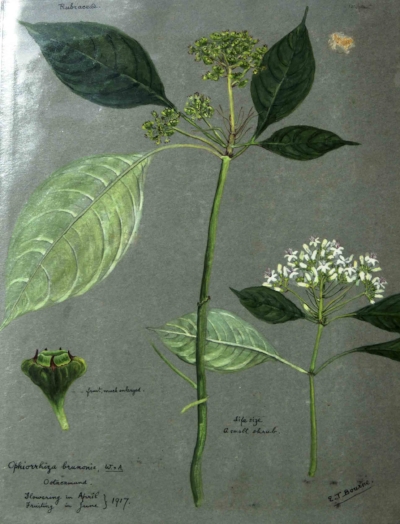

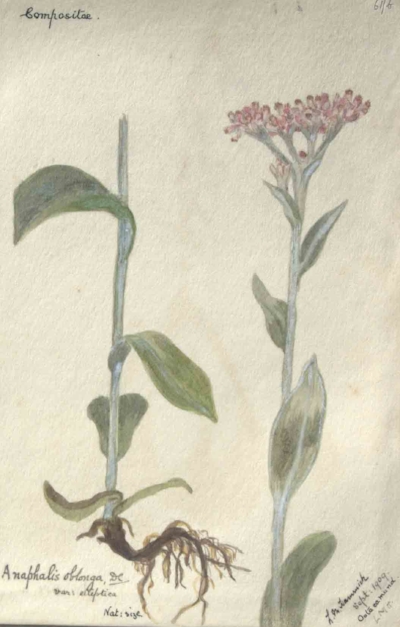

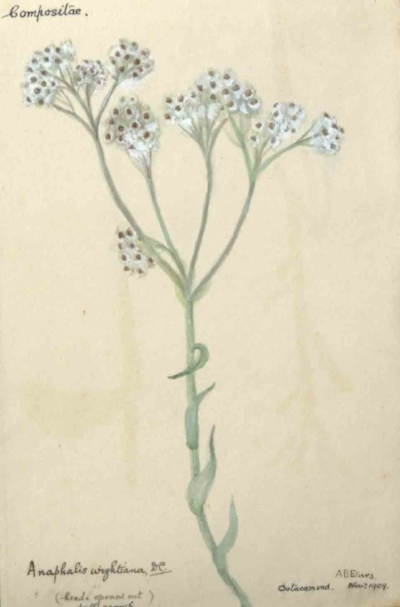

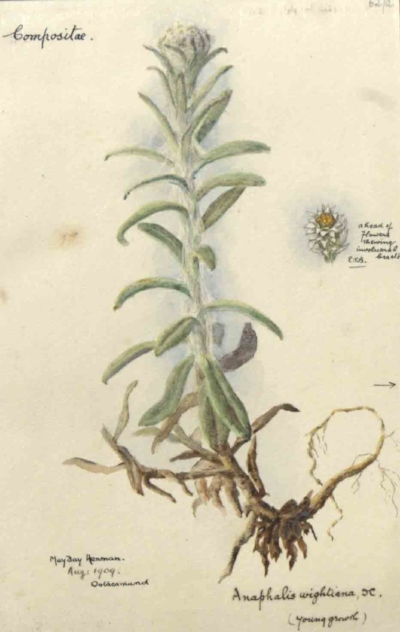

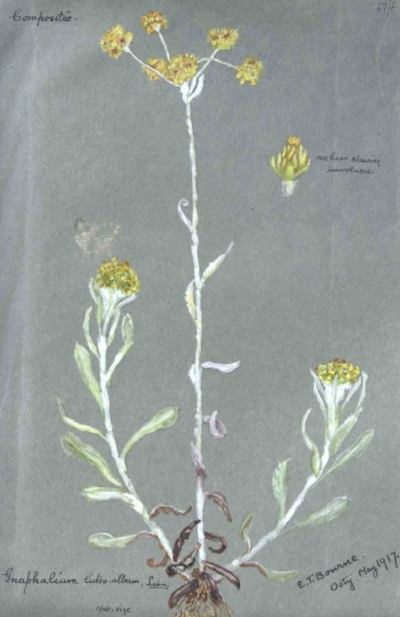

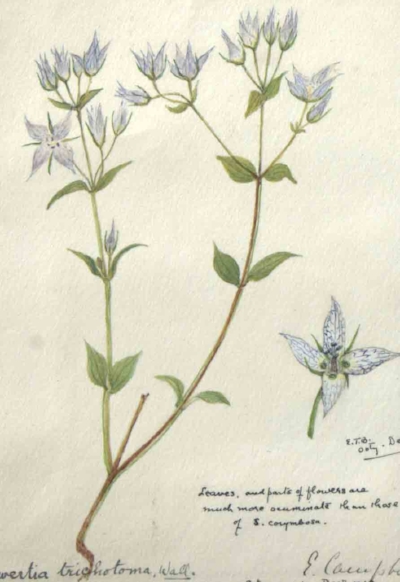

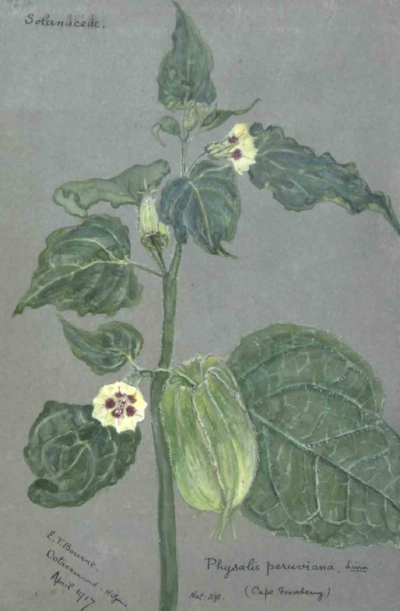

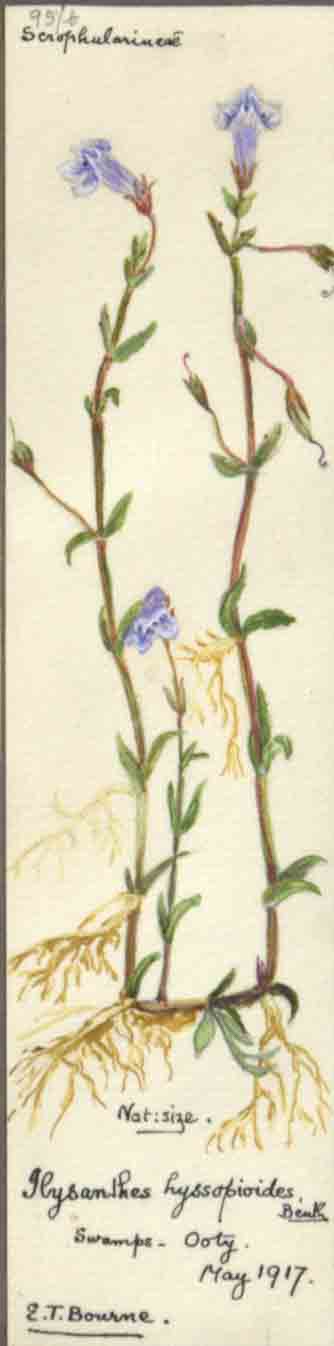

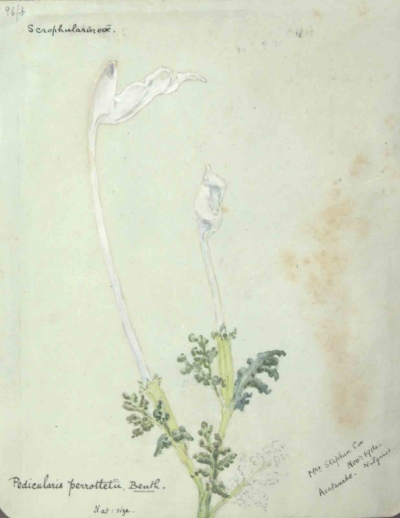

Botanical Watercolors: Amateur Artists

NILGIRI ARTISTS, early 20th century

LADY EMILY TREE BOURNE'S ALBUM (Ootacamund Flowers)

Miss Askwith, Miss Biddy Atkinson, Mrs. Bannerman, Miss Nora Bourne, Mr. Ray Bourne, Mrs. Sam Bourne, Miss Callow, Miss Eva Campbell, Miss Winnie Campbell, Lady Cardew, Miss G. Cruickshank, Mons. Decubes, Miss Helen Donovan, Mrs. [A.B.] Weston Elwes, Miss Gell, Miss Lorna Hammick, Miss Dot Hammick, Mrs. [M.F.] C.H.Harrison, Dr. Alfred Hay, Mrs. [Nora] Henderson, Miss Mayday Henman, Mrs. {Hope] Horne, Lady Lawley, Miss Cecilia Lawley, Lady Meyer, Mrs. George Romily, Miss Charlotte Romilly, Miss Nora Rowson, Miss Marjorie Stenson, Miss Wiseman

SHEMBAGANUR TEAM

Sacred Heart College, Shembaganur

August Sauliere

Aloysius (Louis) Anglade

Emile Gombert

Alfred Rapinat

Joseph Pallithanam

Eugene Armand-dit Georges Foreau

K.M.Matthew

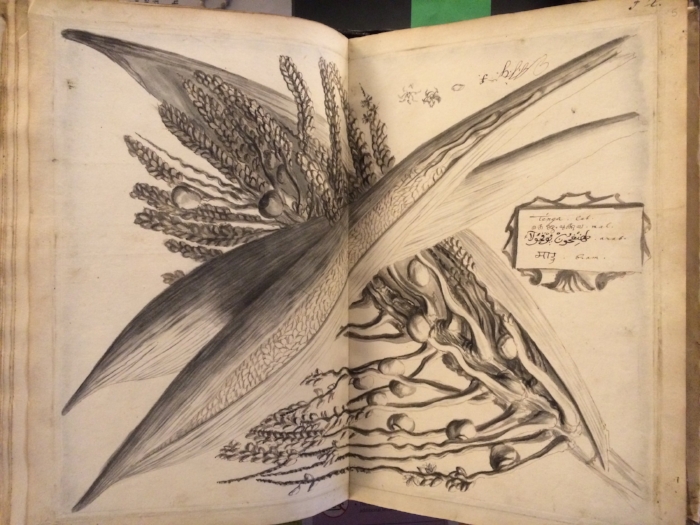

By the late 19th century, botanical illustration in India was a thriving genre, influenced by new demands of tropical botany, imperial garden collections at Kew and Edinburgh, and not least, what had come to be termed as the ‘golden age of botanical illustration’ in the West. Following early master artists in Europe such as Georg Ehret and Ferdinand Bauer, the convention in botanical art the world over began to shift emphasis to the scientific record and botanical accuracy of plants drawn in their natural habitat. Globally identifiable plant drawings (cut-stem, white ground, individual specimens) whose primary purpose was not aesthetics but taxonomy, the identification of plants in a post-Linnaean world of botanical science.

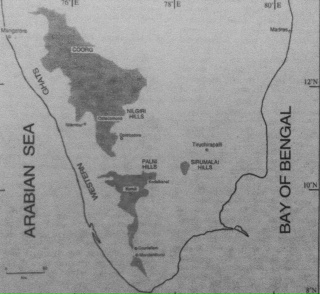

And here colonial-era botanical art of the South Indian hills tells a very different art historical story of hybrid East-West encounters. The Nilgiris – or rather the Neilgherries (as the Blue Mountains were spelt and therefore seen in the early 19th century) was well documented by its first British residents. But it’s the art that shines a unique light here. In extensive but little known collections of botanical art, these early settlers depicted the Neilgherries as both botanically strange as well as intimately familiar. Strange in that the foreign flora included exotic native plants unique to its slopes, chief among them being the blue wildflower shrub Kurinji, Strobilanthes kunthiana, which blooms only once every 12 years and gives the Nil Giris, the Blue Mountains, their name. Familiar in that the vegetation and landscape of these open grass-covered hills reminded these homesick Britons of Blighty! Whether the comparisons made were with rolling Sussex downs or Scottish highlands or even – for those who hated the Neilgherries’ rainy season – with Lusitanian gloom! The cool, temperate hill climate was pronounced ideal for British constitutions. And so the hills became further domesticated even as they were colonized. By the late 19th century, the Neilgherries had become – sometimes even more than was possible in the narrower, rockier, steeper Himalayan hill stations – idyllic little pockets of England-in-India providing much needed green respite from the burning alluvial plains and the hot Deccan plateau.

As to the (mostly Tamil) hill town names, these new residents weren’t called the “abbreviating Saxons” for nothing. Ooty was the shortened version presumably when their tongues couldn’t wrap easily around Othakal-mund, the original Toda name, and Ooty it remained. And Ooty was where they flocked in droves after John Sullivan, Collector of Coimbatore, discovered the hill station in 1819 following his scouts’ glowing reports while surveying the mountains. Sullivan settled in to Ooty a year later, and others soon followed. The population doubled, then tripled over the century and those who came, stayed. And summered. By 1870, the annual summer exodus regularly included the Madras and Bombay Presidencies and their accompanying bureaucracies, all of whom escaped en masse to the hills – or as Gandhi had mocked, to govern from the 500th floor!

And those who stayed and summered in Ooty, gardened – especially once they discovered the Neilgherries could grow everything their floral and vegetal nostalgia desired: strawberries, mulberries, and all manner of temperate zone fruit; primroses, asters, hollyhocks, mignonettes, laburnums, geraniums, a profusion of roses. And the vegetables – string beans, tomatoes, potatoes, artichokes, lettuce, radishes, turnips – as well as what the Company (and later the Crown) called products of ‘economic botany’: tea, coffee, cinchona plantations. In the 1840s, Robert Wight, the director of the Madras botanic gardens, was sent to Ooty by the Madras government to study crops appropriate to the temperate climate of the Neilgherries – presumably to explore large-scale cultivation for the East India Company.

In 1848, the new public Ootacamund botanical gardens were formally laid out on the lower slopes of the Doddabetta peak by its architect, John Mcivor (the man who successfully brought cinchona to Ooty), with the help of a gardener from London’s Kew Gardens. Today, it is known as the Government Botanical Garden, one of Ooty’s most visited attractions and one of the oldest surviving botanic gardens from colonial India. And its peculiar patchwork horticultural history can be pieced together from some of the existing structures on its vast grounds — the glass Fern House established in 1895, which bears Mcivor’s name; the well laid out plant beds and partierres in the Italian Garden dug by PoWs from WWI; the Lower Garden, which was originally the Marquis of Tweedale’s vegetable garden for Ooty’s early British residents. And most poignantly of all – the three surviving Toda huts (dogles) at the very top of the hill that serve as tragic reminders, like some frozen ethnographic diorama, of the tribal groups to whom this land once belonged, and from whom Sullivan apparently bought it for a song.

From the point of view of botanical art, the Ooty Botanical Garden quickly became a hotbed of activity. It was the epicenter for a whole host of plant portraits drawn by amateurs – a nexus of botanists, women, gardeners, hill residents – which offered an entirely new way of thinking about encounters between British botanists and local artists. These artists were indeed local residents of the Nilgiris’ towns, but (unlike other regions) were not native painters with influences from the vernacular traditions or Tanjore and textile arts. Rather, they were keen amateur botanists and thus probably familiar with the European traditions of botanical art with their cut-stem, white-ground and isolated compositions and their notions of Western perspective and recession.

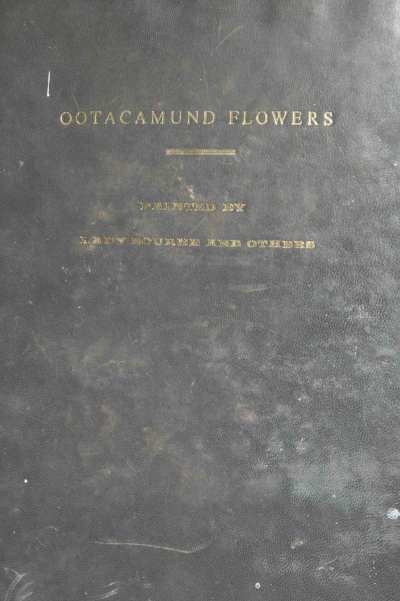

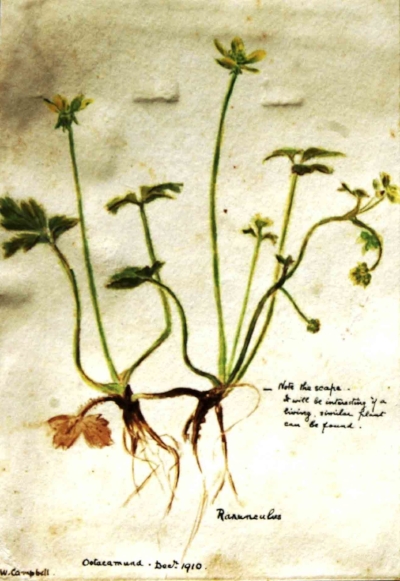

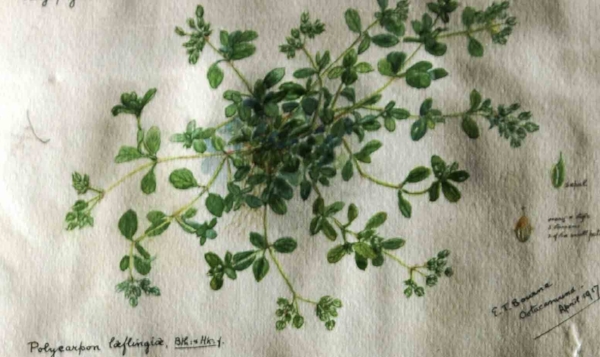

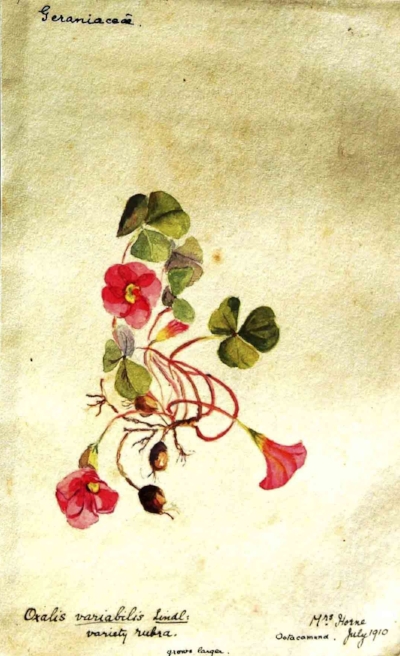

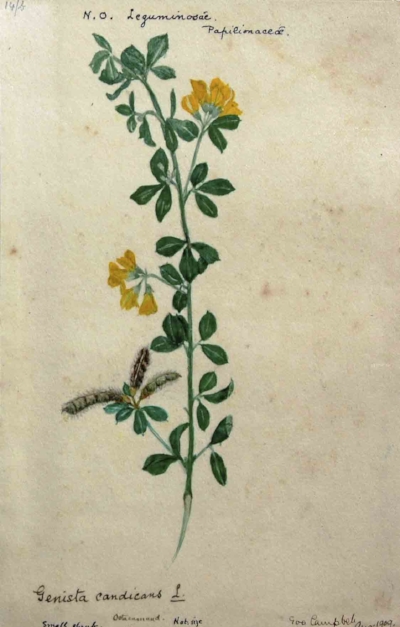

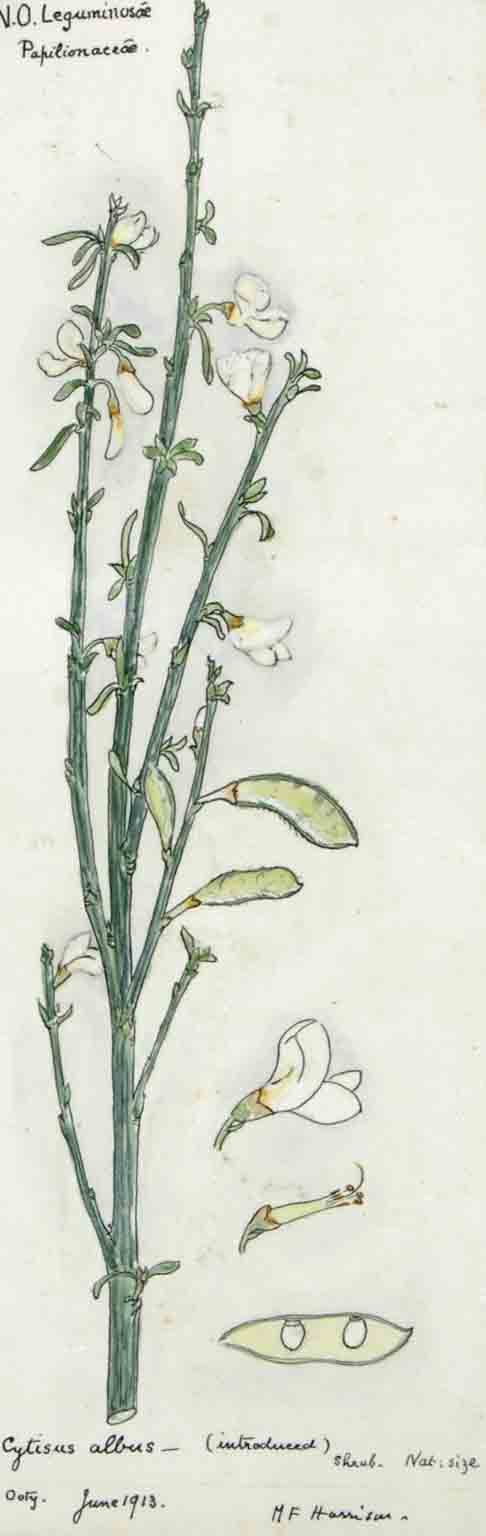

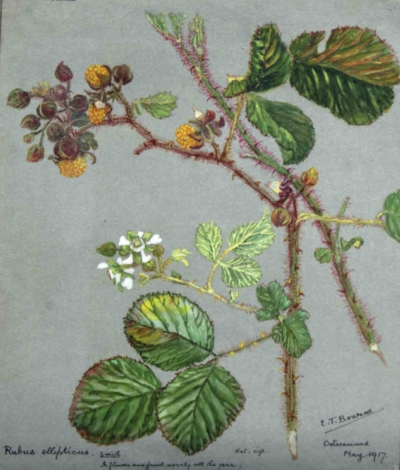

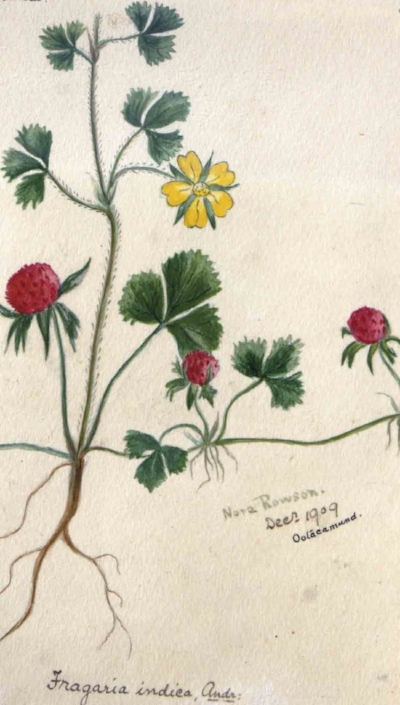

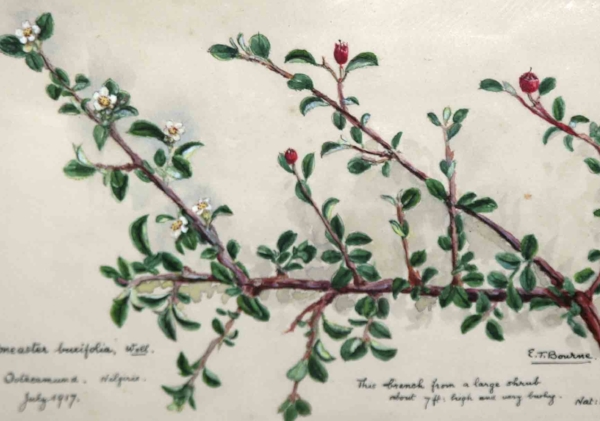

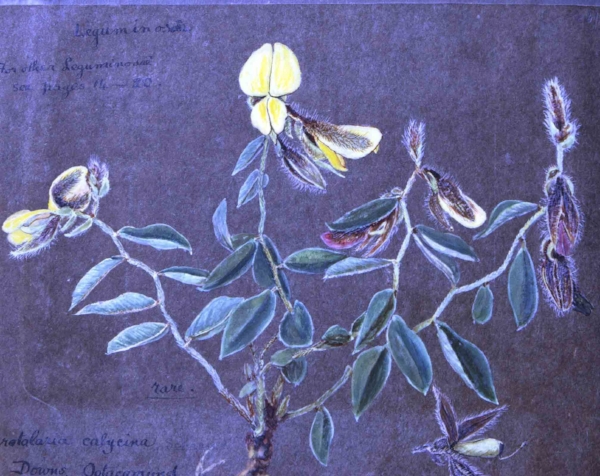

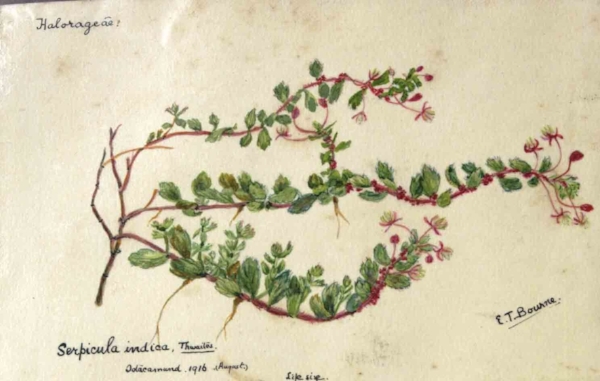

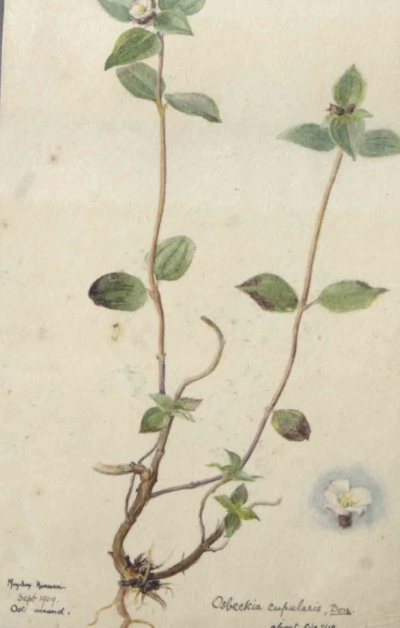

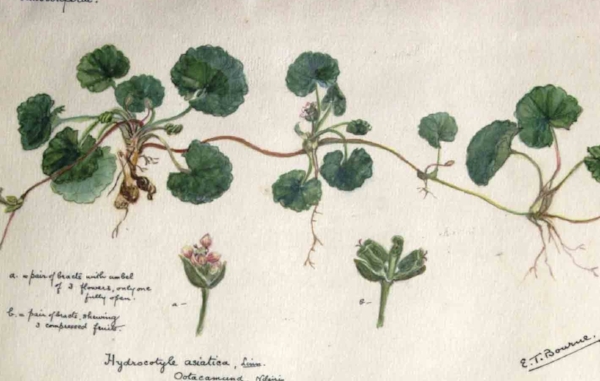

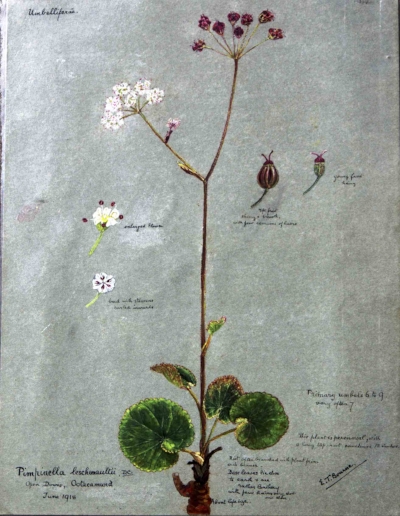

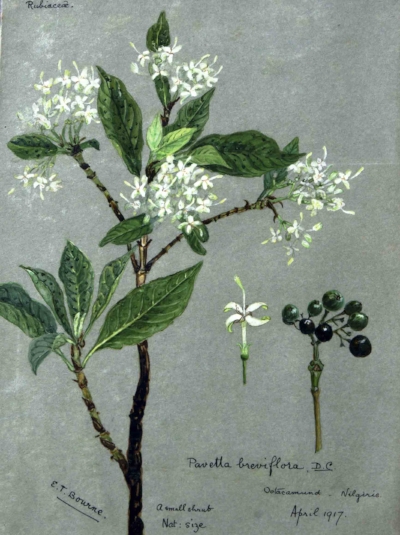

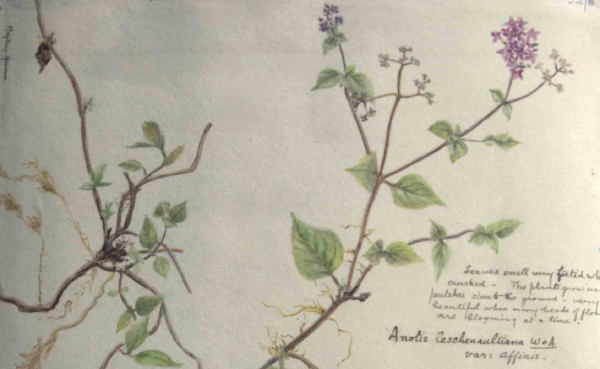

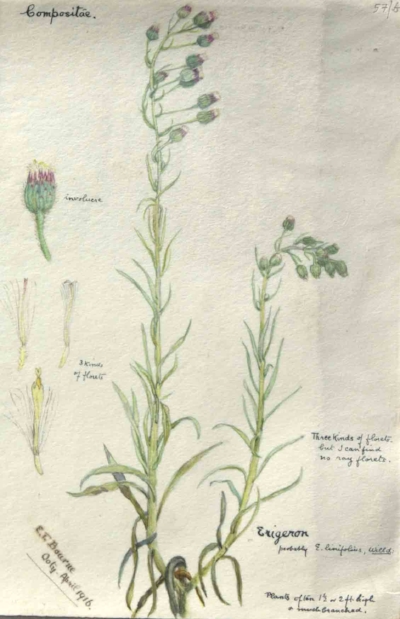

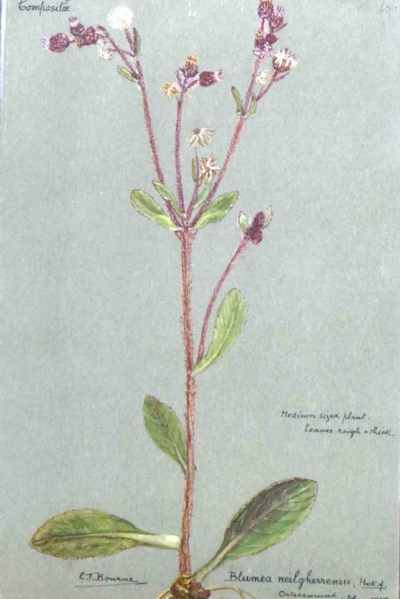

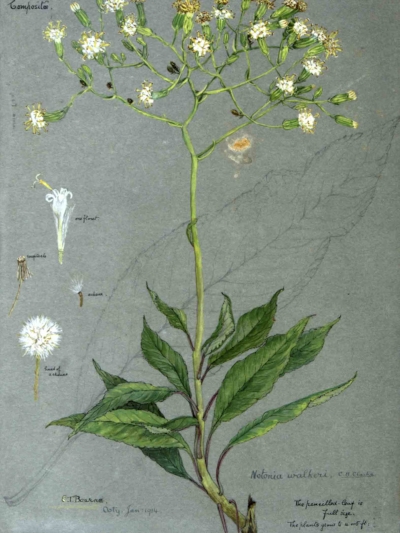

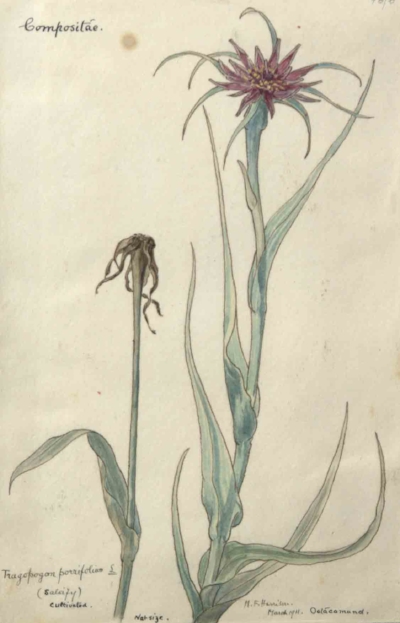

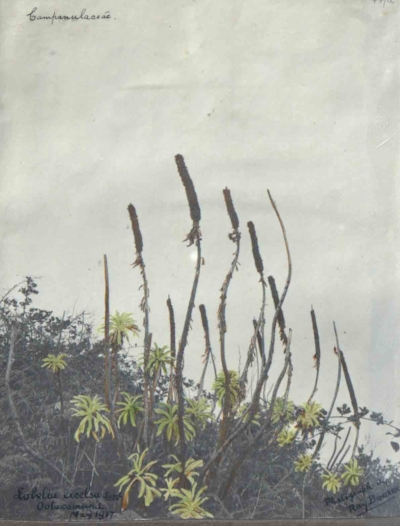

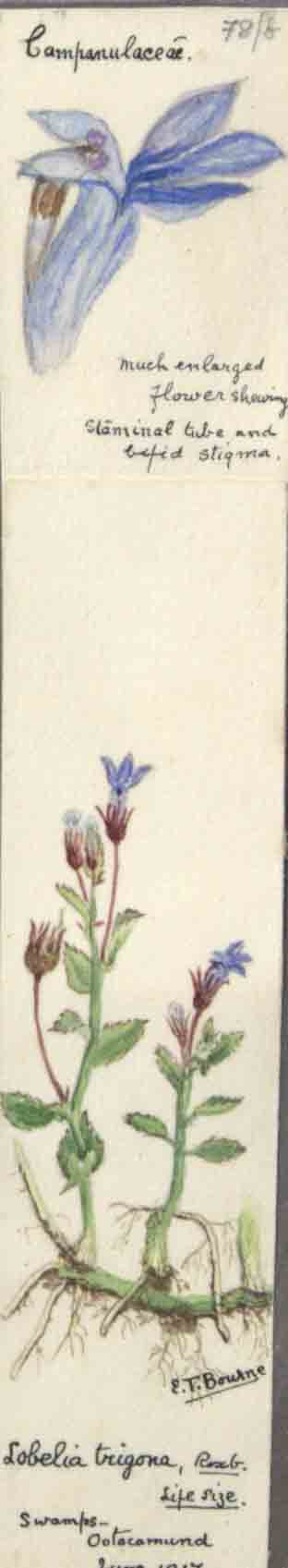

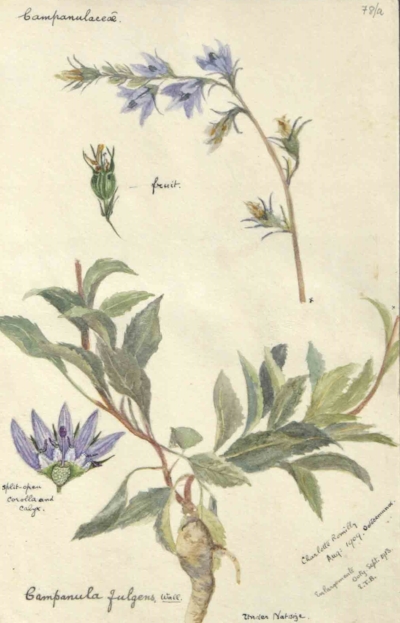

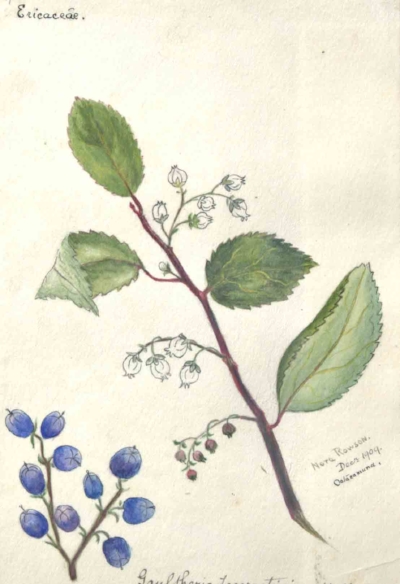

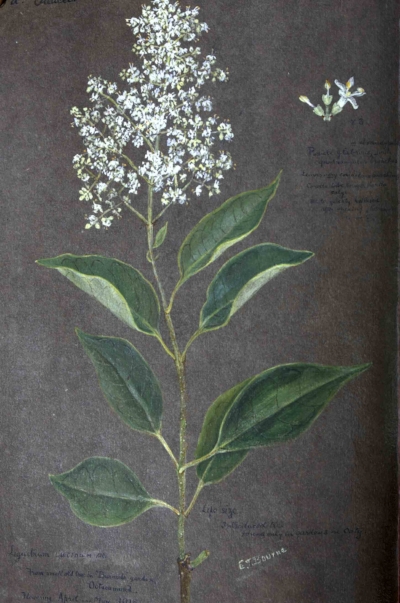

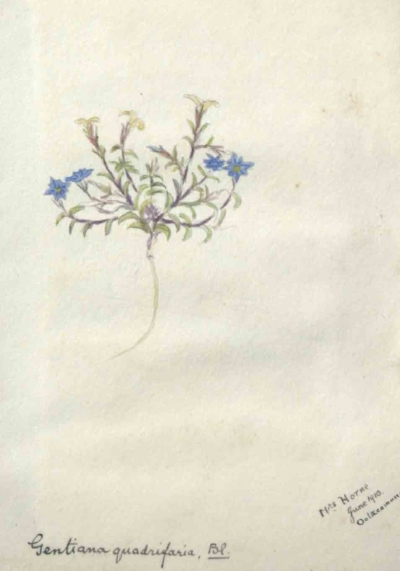

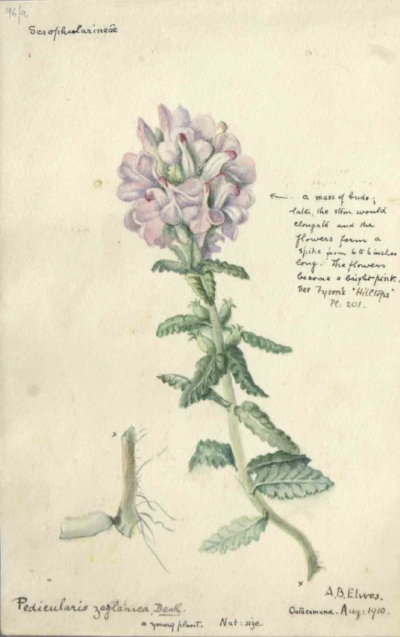

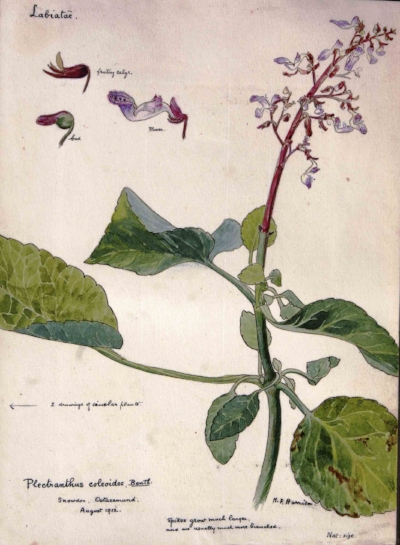

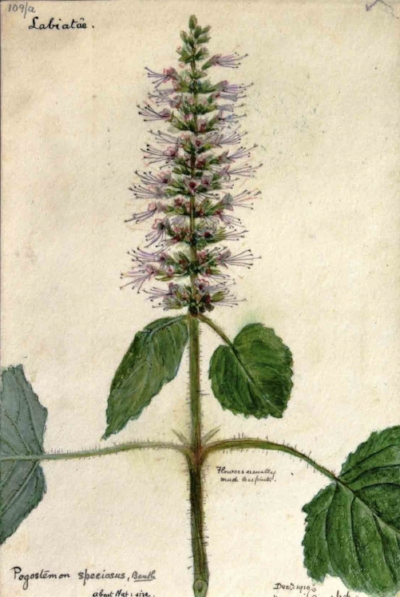

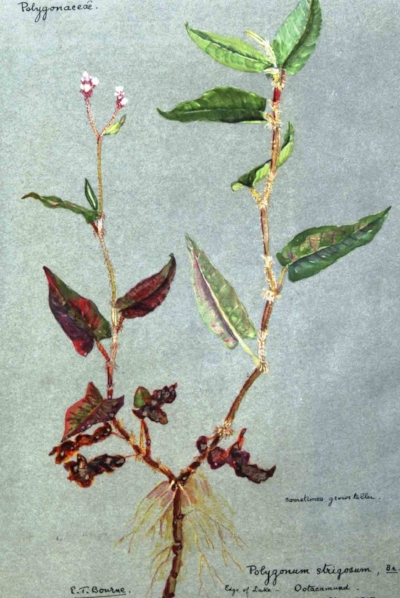

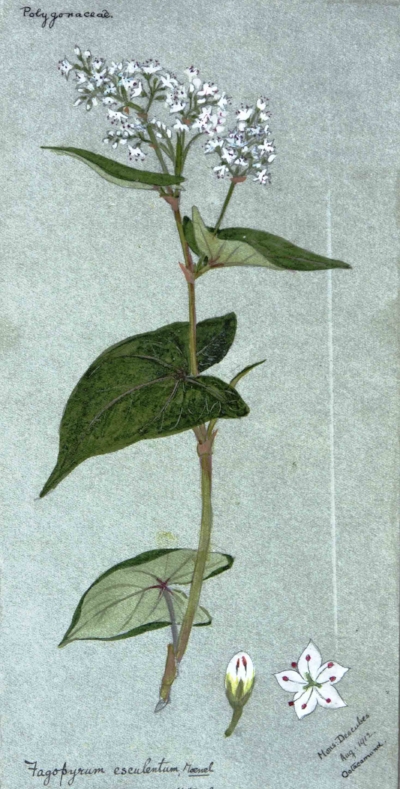

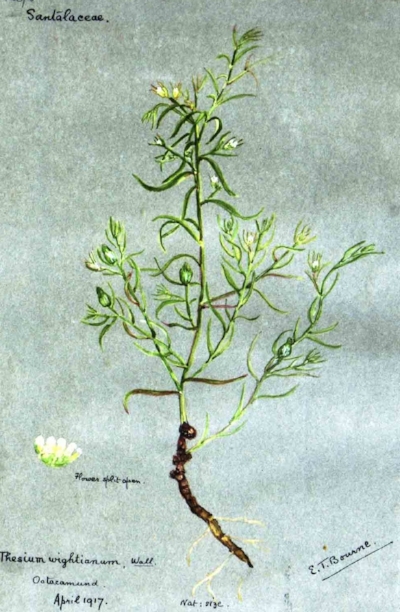

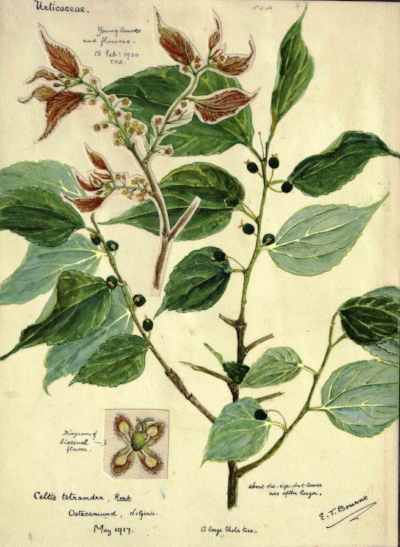

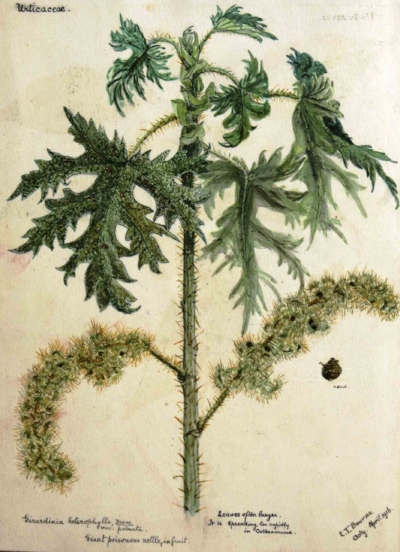

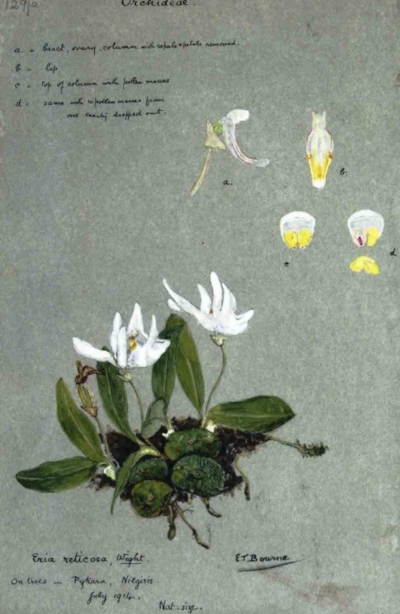

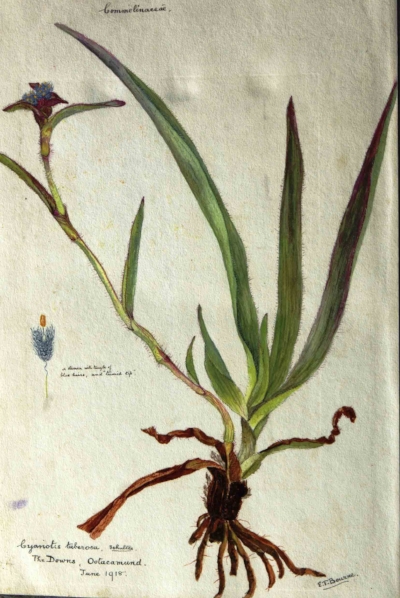

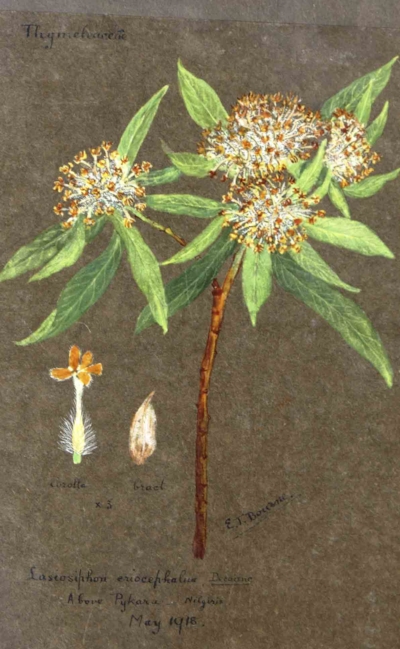

Of all the art that came out of the Ooty garden, the best known was the fascinating collection of botanical paintings from the early 20th century called the Bourne album. Titled Ootacamund Flowers, the Bourne album was commissioned between 1910-15 by Lady Emily Tree Bourne, wife of Dr. Alfred Gibbs Bourne, then government Botanist in Madras – and no mean botanist and artist herself. Apart from Lady Bourne’s own illustrations, the album also included contributions by a network of amateur artists and botanists, all European women, who spent their summers in Ooty, Kodaikanal and Kotagiri. Some of the Bourne drawings found their way into print through the definitive floral survey of the region, P.F. Fyson’s Flora of the Nilgiris and Pulney Hills (first published in 1921 with a second edition in 1932). And around this time, Lady Bourne also made her way to Kew Gardens to personally deposit the Bourne herbarium in London.

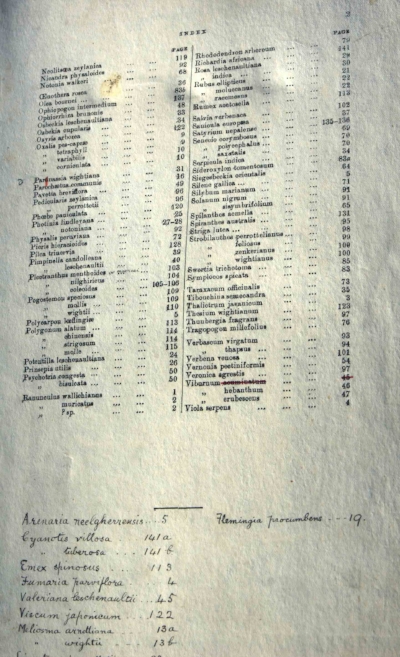

So, what do we know about this volume of original, unique, and unpublished paintings? That there were approximately 225 paintings, drawn and painted by a group of approximately 30 European women, all amateur naturalists and artists, bound into a volume and presented to the Madras government in 1917. That they were small detailed watercolors, of consistently high quality per the botanical art convention of the day, painted on cream-colored card and pasted into a brown album. That they included most of the indigenous flowers of the Neilgherries (index). Some have suggested that these paintings could be considered examples of the Kampani kalam style — given that its definition describes a hybrid Indo-European art style that arose when East India Company naturalists and administrators commissioned botanical or ethnographic paintings from native Indian artists trained in xxxx. With Ootacamund Flowers, however, its not so clear that Company School fits. While the Bourne botanical paintings certainly derive and are probably inspired by Kampani kalam to some degree, the album comes along too late to be anything but late, very late, Company School. If anything, the paintings are more influenced by Western botanical art conventions of the day. Besides, the Bourne paintings were all done by European, not Indian, artists.

From Lady Bourne’s notes in the preface, we know that the volume was presented by her to the Madras Government in 1917 (General Order No. 3247). And the artists themselves are listed below, as given in the volume.

Miss Askwith, Miss Biddy Atkinson, Mrs. Bannerman, Miss Nora Bourne, Mr. Ray Bourne, Mrs. Sam Bourne, Miss Callow, Miss Eva Campbell, Miss Winnie Campbell, Lady Cardew, Miss G. Cruickshank, Mons. Decubes, Miss Helen Donovan, Mrs. [A.B.] Weston Elwes, Miss Gell, Miss Lorna Hammick, Miss Dot Hammick, Mrs. [M.F.] C.H.Harrison, Dr. Alfred Hay, Mrs. [Nora] Henderson, Miss Mayday Henman, Mrs. {Hope] Horne, Lady Lawley, Miss Cecilia Lawley, Lady Meyer, Mrs. George Romily, Miss Charlotte Romilly, Miss Nora Rowson, Miss Marjorie Stenson, Miss Wiseman

From what we know, the Bourne album was in the Ootacamund garden main library until at least 2011. In personal communication, Henry Noltie (curator extraordinaire of Indian botanical art, and author of marvelous books on Hugh Cleghorn and Robert Wight) tells me he’d seen the volume in 2002. Eugenia Herbert’s reference to the Ooty album is in her delightful book, Flora’s Empire, published in 2011. K.M.Matthew, the pioneering botanist at St Joseph’s College, Tiruchirapalli wrote in his informative Huntia article that the Bourne album was in the Ooty office in 2000. As did art historian James White in his survey of botanical art collections in India, written before his untimely passing. The album is not currently in the library but its images have been kindly given to me by Dr. Ramsunder.

30 of these paintings are presented here, with the sample including one image (at least) by each of the amateur artists involved in creating these paintings. Collectively, they offer an unparalleled botanical view of the Neilgherries in this period. (Matthew - cite from article).

If the album has an art genealogy at all, it may have more in common with the line of amateur botanical paintings by intrepid female travelers to India such as Marianne North and Marianne Cookson. Or going further back, with botanical art collections commissioned by the wives of British administrators since the 18th century – for example, Lady Impey’s extraordinary collection of 300 paintings by indigenous artists in Calcutta, and the equally solid South Indian collections of botanical art put together by Lady Canning (19 volumes!) and then Lady Stanley in the early 20th century.

But taken together, the beautiful signed paintings of the Bourne album also remind us that there’s no missing link like the link that is no longer missing. Image archives or digital copies of lost originals are better than no archives at all, but in the long run, there’s no better archive than a found one. There’s probably a reason that curators are called keepers, but with the volume and pace of loss in Indian archives, one must also carve out a space for the ‘finders’ of lost objects, lost records.

Botanical art speaks volumes. If we accept that the Nilgiris and Ooty have changed rapidly over a century, we might also accept that 100-year old botanical art is often the best record we have of this vanishing natural history. So for the sake of archival rescue, for the sake of our heritage, for the sake of gone and going flowers in the rapidly morphing Blue Mountains, art originals bring back the true value of the ‘weight of a petal’ as it lives, dies and evolves. Libraries and flora – and even botanical art, however sublime – are no substitutes for the flowers they represent on the page, in print. If we can save even a small forgotten fragment of this precious archive, we transform loss into partial immortality for the ages. To use an alchemical metaphor, we manage – against all odds – to turn dross into gold. We manage to gild the proverbial, and often endangered, lily.